Building a Cultural Epicenter

Editor's Note: In advance of our Inclusive Economic Prosperity in the Midwest convening, we're highlighting stories from the region. This article was originally published in bMag, a publication by the Bush Foundation. Photography is by David Ellis.

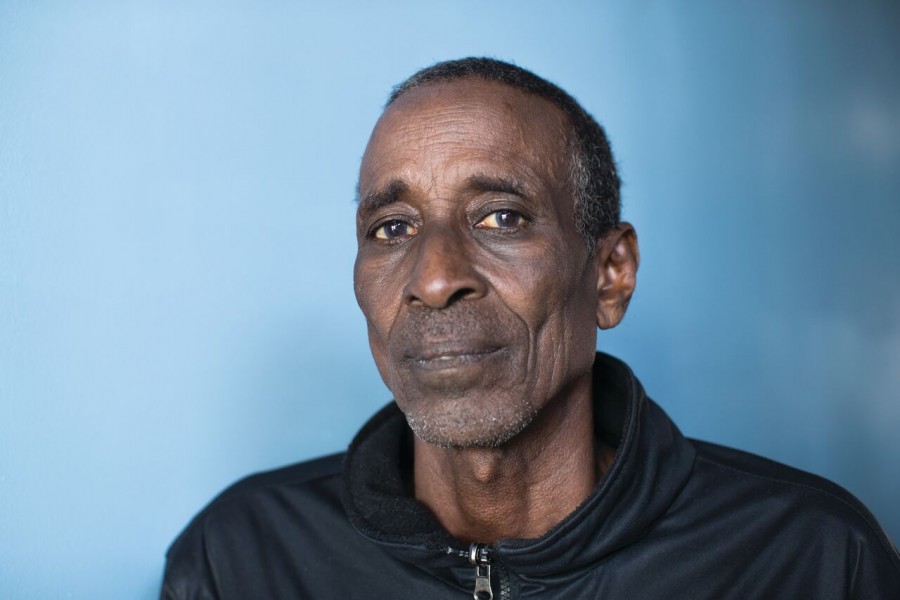

On an autumn afternoon in 2017, Abdirizak “Zack” Mahboub (BF’10) stands outside the glass-walled front of the two-story building that will soon become the Midtown Plaza Mall in downtown Willmar.

The former small-town Minnesota furniture store lacks curb appeal, but Mahboub’s vision fills in the blanks with the same contagious enthusiasm that caused the local Somali community and players in finance and community development to see it, too.

The road to developing a home for Somali businesses and services in this growing immigrant community has been winding. It takes a bridge builder to see a future in which people of many faiths and languages come together around a common goal — a vision that crosses barriers of entrenched mis-understanding and fear. In Willmar, Minnesota, Mahboub has shown his mastery both for seeing the vision and bringing it to life.

Outer Space & Small-Town America

Born in Somalia in 1960, Mahboub’s first inkling of life in the United States came when he was an elementary school student in Mogadishu. His father took him to see an Apollo 11 prototype and pictures of American astronauts walking on the moon. While there, he decided to travel to the United States one day and become an astronaut himself.

In 1981, Mahboub persuaded his father to allow him to come to America to attend college, and he eventually earned a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering from Massachusetts’s Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston. Several years working as an information analyst for Electronic Data Systems, as well as starting a family, kept Mahboub in Massachusetts until he followed an employment opportunity for his wife, Sahra, and relocated in 2003 to Lewiston, Maine, home to a fast-growing community of new arrivals from now war-torn Somalia. In Lewiston, distrust and hostility awaited the Somali refugees. Their language, dress and religion were all deeply unfamiliar to the nearly all-white community.

Amid heightened tensions after 9/11, the mayor of the city wrote an open letter to the Somali community discouraging future immigration. The message was clear: Somalis were not welcome in Lewiston.

Mahboub embraced a public role of mediator after the mayor’s declaration.

Back in Boston, Mahboub had founded a Somali community-based service organization, and in Lewiston, he had already opened a Somali restaurant — the first of its kind in the state. He was clearly vested in his respective communities. It was simply a matter of time before his passions and skills led him to take on an even larger role within and for his community.

Following the mayor’s letter, a small number of hate groups publicly demonstrated, and an even larger contingent of Somali supporters came together. During this upheaval, Mahboub emerged as a trusted, authoritative voice for his community, and the story gained attention from around the world as a symbol of quickly changing times.

A Path Develops

“An improbable migration has turned into a large-scale social experiment,” wrote the New Yorker, after the town of Lewiston and the mayor’s declaration became the subject of a documentary called “The Letter.” Mahboub delivered much-needed connection and understanding — bridging communities in a spirit of reason and calm — in both the documentary and the defused crisis.

A few years later, after his wife visited the Twin Cities and fell in love with the area, Mahboub and his family moved to Minneapolis, joining its major Somali American community. He connected as a volunteer with social service organizations and in 2008 became the executive director of the Cedar Riverside Neighborhood Revitalization Program (CRNRP) in Minneapolis.

“It seemed really clear that he had a passion for a society to literally work for everybody,” says John Bueche, who hired Mahboub while serving as Board Chair of CRNRP. “With Lewiston in his background, we thought that he might be able to follow through with that — and it turned out to be entirely true.”

Bueche cites Mahboub’s uncanny ability to maneuver among tense factions to bring about mutually beneficial results. In an East African community, for example, Mahboub facilitated local teens to engage in the arts during a spate of gun violence in their Minneapolis community. Bueche also lauds Mahboub’s ability to bring Somali elders into engagement and decision making.

“I feel that I have a privilege being in this country,” Mahboub says, “from first living on the East Coast and now, later in life, coming to Minnesota. It has given me an understanding of American culture and different ethnic groups. It gave me insight into how all ethnic groups evolve generation after generation.”

Mahboub began to realize that he needed more tools to continue on his path of advocating for Somalis and East Africans, so he applied for a Bush Fellowship, which he was awarded in 2010. His immediate goal was to pursue a Master of Public Affairs degree from the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey Institute — a course of study that examined the intersection of economics, public policy, sociology and political thought.

“Most [Somali immigrants] become U.S. citizens and are eager to be part of the American community,” Mahboub wrote in his Fellowship application, “but they lack understanding of political, economic and social systems that impact their livelihood.”

At the time he applied for the Fellowship, Mahboub knew he needed to elevate his knowledge of economics and politics in order to truly effect change for the Somali community in the Twin Cities. Little did he know that fate would take him a couple of hours west along quiet rural roads.

East Africa Meets Southwest Minnesota

After Mahboub earned his master’s degree, he was at a crossroads: He could stay in Minneapolis or follow emerging East African communities with the African Development Center — a pioneering community-based business and lending institution directed by the late Hussein Samatar (whose election to the Minneapolis School Board made him the first Somali American in the nation to win elected office). Mahboub chose the latter, which meant that in 2011, he moved his family to Willmar, Minnesota.

Willmar is home to about 20,000 residents in southwestern Minnesota’s Kandiyohi County.

Willmar is home to about 20,000 residents in southwestern Minnesota’s Kandiyohi County.

Settled on the ancestral land of the Dakota people, a convergence of agricultural riches and a stop on the railroad enticed Scandinavian immigrants beginning in the 19th century. Once best known for a bank robbery by the Machine Gun Kelly Gang in 1930, Willmar is now associated with more lawful pursuits, like its thriving technological campus and industrial park, both major players in the local economy, and a Jenny-O turkey processing plant that provides an abundance of jobs.

About two decades ago, the community diversified further with the arrival of Latino immigrants attracted by agricultural-based labor. Despite challenges, members of that community began to put down roots, establish businesses and buy homes. In the last decade, an East African community has also begun to establish itself in Willmar.

“Where we are today with the East African community is where we were about 20 years ago with the Latino community,” says Ken Warner, president of the Willmar Lakes Area Chamber of Commerce.

From Setback to Opportunity

Within a year of moving to the town, Mahboub founded the West Central Interpreting Service, a multi-lingual business with a network of subcontractors specializing in language interpretation for non-English speakers in their interactions with healthcare, schools, social services, courts and business. This entrepreneurial start-up thrived and has expanded service throughout the southwestern Minnesota region.

The Willmar East African community’s own entrepreneurial efforts were staring down a major setback in 2013. The Centre Point Mall was a downtown home to commercial tenants serving the Somali community, and when it was sold by the bank that owned it, a number of businesses — including a grocery store, community coffee shop and four additional establishments — had their leases terminated immediately.

The Willmar East African community’s own entrepreneurial efforts were staring down a major setback in 2013. The Centre Point Mall was a downtown home to commercial tenants serving the Somali community, and when it was sold by the bank that owned it, a number of businesses — including a grocery store, community coffee shop and four additional establishments — had their leases terminated immediately.

“Zack tried to negotiate between the owner of the mall and the shop owners,” says Abdusalaam Hersi, who has known Mahboub since Lewiston and now owns the Salaam Transportation Co. in Willmar. According to Hersi, the negotiations weren’t successful, but perhaps that only added fuel to Mahboub’s quest for a space to call their own.

A lot of East African businesses invested and lost. That’s when myself and others started to ask: ‘What is a permanent space where these people can flourish?’ Zack Mahboub

Demonstrating Community Value

Willmar resembles many small, American communities. Much of the business and building activity these days is taking place on the periphery of town. Downtown buildings are in various states of aging, some neglected by absentee landlords. Willmar could be said to be doing better than most small midwestern towns, but one can sense an uncertain future on its streets — a question of whether the community’s distinct history will endure.

In the middle of downtown is a two-story, nondescript hulk that reveals little of its history as the Erickson Building, the former home to a multi-generation furniture store that closed in the mid-1990s. Then the building became a manufacturing and administrative branch for an overseas electronics company, but that pulled up stakes a few years ago, too. Mahboub, on the heels of the closure of multiple Somali businesses at the Centre Point Mall, saw the possibility for a new market center based on ownership.

“The first time Zack gave me a tour, he was walking with this great enthusiasm,” says Diana Anderson, president/CEO of the Southwest Initiative Foundation, a major regional development and investment organization. “Early on, it was difficult for anyone else to see his vision because the building was in a state of great disrepair.”

By this time, Mahboub had established himself as a solid figure in the Willmar community because of his entrepreneurial success as well as his eagerness to serve as a community ambassador. He and Sahra were constantly active and visible, making connections and hosting presentations and workshops where they explained details of Somali culture and took questions from community members eager to learn about the newcomers in their midst.

By this time, Mahboub had established himself as a solid figure in the Willmar community because of his entrepreneurial success as well as his eagerness to serve as a community ambassador. He and Sahra were constantly active and visible, making connections and hosting presentations and workshops where they explained details of Somali culture and took questions from community members eager to learn about the newcomers in their midst.

"So many of us are Zack believers, and we want him to succeed any way he can. He’s my go-to guy. I can ask him any question about the East African community, and he’ll explain it to me. When that happens, I’m learning from a friend as well as a mentor." - Ken Warner

Build It & They Will Come

This goodwill got the ear of lenders and potential supporters for what was taking shape as the Midtown Plaza Mall. The 18,000-square-foot building was in rough shape but had good structural integrity, and its owners essentially released it to the community via Mahboub. However, the rehab of the building wasn’t going to be cheap or easy, so a strong economic case had to be made in order for the project to proceed.

“One of the things that I really appreciate about Zack is that he views his work from an asset-based perspective,” Anderson says. “For instance: There isn’t really a culturally appropriate place in Willmar for the East African community to host weddings. Zack talks about the economic impact of that, how dollars leave the community when Somalis have to go to Minneapolis to hold a wedding or purchase things they need. Zack is coming from a place of positioning people to succeed and growing the economy for the entire community.”

Mahboub worked with local allies in government and economic development to put together a funding plan to launch renovation on the building that includes new electrical wiring, structural enhancements and extensive interior renovations.

“It was, to be honest, hard to sell to the bank,” Mahboub says. “The East African economy in southwest Minnesota has not been on the radar of the banks and the financing world. It is a matter of thinking about utilizing the power of these new immigrants breathing life into businesses and downtowns.”

Creating a New Center

“I was a little skeptical at first,” says Laura Warne, president of Home State Bank, a major investor in Midtown Plaza. “Not because of the tenant base, but because that’s a big building and it’s old. But we began to talk in terms of how to help him accomplish this goal and vision of a badly needed retail space for downtown tenants.”

A group of funders put together roughly $500,000 to renovate the property, with stakeholders including Mahboub and Sahra, Willmar-based Home State Bank, the Southwest Initiative Foundation based in Hutchinson, and the Kandiyohi County Economic Development Commission.

With a goal of having street-level businesses in operation and thriving by January 2018, it was ambitious. Much of its strength is in the diversity of the small businesses that make up the commercial core on the ground level. Among others, the mall aims to include:

- Ainu Shams Grocery, the mall’s anchor tenant, which specializes in Halal meats and other goods for the East African community. Ainu Shams has been growing in its small Willmar storefront so quickly that it has been forced to keep cold storage off-site. Here, all operations are under one roof, with a small dining area for coffee and snacks.

- A hair salon for East African women, with culturally appropriate partitions and dividers.

- A clothing store for children.

- A shop for repair and sales of consumer electronics.

- A beauty products shop for women.

- A self-service laundromat.

Redoing the building’s wiring and installing fresh walls and amenities for these businesses was the first phase. Phase two included repairing the building’s large elevator, which will increase access to second-floor offices that companies like Mahboub’s West Central Interpreting Services and Salaam Transportation have already begun to fill. The office level is already finished, with a communal kitchen and a conference room.

“Now that I have an office there, we see so many people coming in every day looking for a place to rent,” says Salaam Transportation’s Hersi. “Even prior to the completion of the project — that tells you that the need is there.”

The third phase of Midtown Plaza will introduce major assets to the East African community in the building’s downstairs, including:

- A gathering center primarily focused as a home for Somali weddings. Because of their length — on average two days, some longer — East African nuptials often aren’t a fit for local rental halls.

- A fitness center exclusively for Somali women, with private facilities to promote exercise while accommodating cultural standards.

- A ground-level mosque with a custom-built entryway to ward off the chill of the Minnesota winter.

Nestled amid antique stores, a coffee shop and other small businesses, the mall is scheduled to be gradually filled throughout 2018. If it lives up to its promise, the Midtown Plaza Mall will be a civic center, a contributor to the community tax base, and most importantly, a hub of East African culture and a symbol of its contribution to the life of Willmar.

Aaron Backman of the Kandiyohi County Economic Development Commission predicts that in two to three years the Midtown Plaza Mall will be a preeminent gathering place. “It will be a place for people to meet, as well as for diverse businesses and their customers,” he says.

“Zack is a bridge builder and navigator, a champion who understands that you have to really respect both worlds,” Southwest Initiative Foundation’s Anderson adds. “We understand that 100 percent of growth in 13 of 18 counties in southwest Minnesota will come from people of color over the next 20 years. How do we create this future that works for everyone? Community leaders such as Zack pave the way.” Anderson cites additional Minnesota Demography Center statistics that predict that in the other five southwest counties, growth driven by people of color will range from 50 to 99 percent.

American Dreamers

“Our immigrants bring value. They want the American Dream — the ability to create a vision and a better life for their kids,” says Backman, who points to projects such as Midtown Plaza as a means for revitalizing downtowns in states of neglect.

None of this has come easily, even with financing in place. Mahboub has had to explain the value of business practices such as longer-term leases that have been met with skepticism in some quarters of his own community.

“We are a broken community after civil war for more than 25 years. All of our institutions have broken down, and a community loses trust and part of its culture when that happens,” Mahboub explains. “I wake up every day wearing my community hat and trying to make some difference. The goal is that, like for other immigrant communities before us, we become part of the DNA of America. But it isn’t going to be easy.”

Tenants and Customers at the Midtown Plaza Mall

Indeed, explains Warne of Home State Bank. “Zack has had to work hard to keep peace, to meet the expectations of the American financing world and to educate his tenant base, who haven’t had any banking experience or experience working with commercial landlords,” Warne says.

“Zack has done a nice job of surrounding himself with good professionals who want him to succeed, and he’s doing it in phases to truly be financially successful.”

This new story also feels like an old one: An entrepreneur steeping himself in business, politics and community reaches out and patiently forges alliances, bringing people together in shared progress and prosperity. Another kind of American dream realized.

"He is kind of the bridge between the mainstream and the newcomers. That in itself is of value, that would be sufficient — but he is also a great asset working to make Willmar better, to make the newcomers’ lives easier, to work with young people and job opportunities. Now there are many Somalis who want to stay in the area and sustain here for a long time." - Abdusalaam Hersi

As Midtown Plaza comes together, with the sound of drills and hammers downstairs, Mahboub learns he has won a 2017 McKnight Binger Unsung Hero Award, an honor with a $10,000 cash prize. He was nominated by leaders from the southwest Minnesota community, and now, on a small table in the second-floor reception area, is a basket of congratulatory flowers. The gift is from the Willmar Municipal Utilities Commission, on which Mahboub serves as secretary, and the card reads: “It couldn’t have been awarded to a better person. Zack, you are an asset to the Utility and citizens of Willmar.”

Mahboub is an asset whose vision points the way toward a better future in southwest Minnesota: a future of increased collaboration, understanding and prosperity for all.