Putting Down Roots

Editor's Note: As a part of our Inclusive Economic Prosperity in the Midwest convening, we're highlighting stories from the region. This article was originally published in bMag, a publication by the Bush Foundation.

Pakou Hang (BF’11) and her six siblings spent much of their childhood rising early to weed and pick cucumbers on the family farm before school.

Those cucumbers, which their parents sold to Gedney Pickles, paid for school tuition.

Hang went on to receive her Bachelor of Arts from Yale in 1999 and her master’s in Political Science from the University of Minnesota in 2008. Even as she kept moving forward, she didn’t stop looking back, and in 2011, she was awarded a Bush Fellowship to investigate the challenges Hmong farmers in Minnesota face in participating in the local foods and sustainable agriculture movements.

Farming has been an integral part of the Hmong immigrant experience ever since refugees started arriving from Southeast Asia in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Today, Minnesota’s Hmong American population is the second-largest in the country, at more than 66,000. Hmong American farmers make up more than half of the vendors in Twin Cities area farmers markets and hold an important place in the Minnesota local-foods economy, which generates more than $250 million in annual sales. But despite their significant contributions to the state food ecosystem, Hmong American farmers typically only earn about 60 percent of what their white counterparts do, and one quarter of Minnesota’s Hmong population still lives below the poverty line.

To learn more about the needs and concerns of Hmong American farmers, Hang engaged in more than 40 one-on-one conversations with them and other community stakeholders. When a national conference of social investors seeking ways to support immigrant farmers came to Minneapolis, Hang hosted a panel discussion on the unique challenges and opportunities of Hmong American farmers.

Vang Moua, a Hmong American farmer who had been facing many of these challenges for decades, was among the stakeholders Hang invited to the conference. She rose and, in her native tongue, told the assembled mix of farmers and investors that she’d been waiting 20 years to have this conversation. “We have to stop waiting for someone to come and save us,” Moua said to the crowd. “We can save ourselves.”

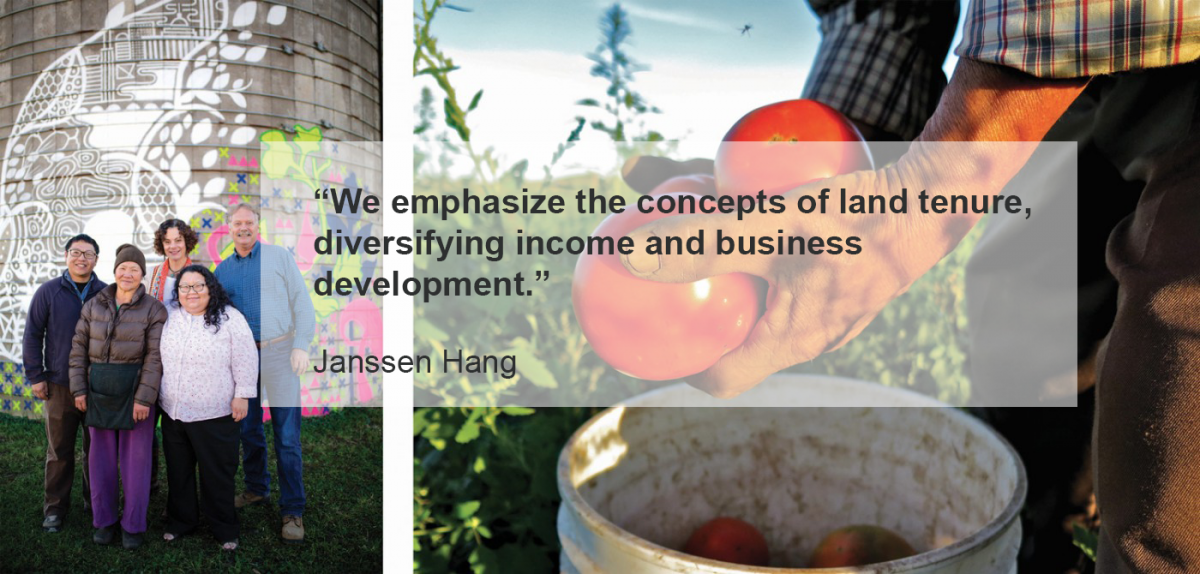

“That remark was the tipping point,” says Hang. “Vang made that comment at the conference on a Thursday. By the following Tuesday, I was incorporating the Hmong American Farmers Association (HAFA).” Hang, along with her brother and co-founder Janssen Hang, created HAFA in 2011 with a mission to advance the prosperity of Hmong American farmers through cooperative endeavors, capacity building, research and advocacy. Since then, HAFA’s efforts have paid off — the association received a 2014 Community Innovation grant and a 2017 Bush Prize.“

"I used to have to bring my harvest back to my house and store it in the garage. Now we have resources available. We have water, coolers and facilities to help us. Our quality of life has changed." Vang Moua

On a chilly October morning in 2017, Moua sits smiling in the renovated farmhouse at the center of the HAFA Farm, a 155-acre research and incubator farm in Vermillion Township, 15 minutes south of St. Paul. She has spent the morning harvesting Brussels sprouts, and her fingertips poke out of her fingerless gloves, covered in the rich soil of the fields surrounding the farmhouse. “I used to have to bring my harvest back to my house and store it in the garage,” she says of the pre-HAFA years. “Now we have resources available. We have water, coolers and facilities to help us. Our quality of life has changed.”

Planting Seeds for Growth

Though the obstacles encountered by Hmong American farmers include access to new markets, capital and credit to optimize operations, and opportunities for training and research, perhaps the most fundamental hurdle they face is land access. Without long-term access at an affordable rate, vegetable farmers can’t grow perennial crops, which yield a higher profit margin than annual crops, or invest in farm equipment that improves efficiency. Lack of land access also leaves Hmong American farmers vulnerable to exploitation.

HAFA has collected stories from farmers who were forced to give up 40 percent of their crop yield to landowners, or who had to allow the landowners to harvest anything they wished from the farmers’ rented plots, free of charge. These modern forms of sharecropping made securing permanent and affordable land a high priority for HAFA.

In 2013, a generous benefactor purchased the 155-acre farm in Dakota County and offered HAFA a long-term lease that would eventually allow the organization to purchase and manage it as a cooperatively owned agricultural land trust — the first of its kind in the country for immigrant farmers. Since acquiring the land, HAFA has remediated the soil, planted waterway pollinator habitats, restored the native oak savanna, added an agricultural well, renovated the farmhouse, and added produce washing and storage facilities. They also started a bee-keeping operation and are undertaking multi-year research to study the effects of various cover crops on water and soil health — just one example of a project that would be impossible without a permanent home.

Hang describes HAFA as similar to a hungry startup: “We set ambitious goals. We’re data-driven, results-oriented and entrepreneurial in our spirit.” When HAFA was born in 2011, its member farmers were earning only $5,000 in sales per acre while their nonimmigrant counterparts were making anywhere from $8,000 to $20,000 per acre. In 2017, HAFA farmers made an average of $11,000 per acre — an increase of 120 percent.

They accomplished this through a creative, determined blending of innovation and commitment to traditional cultural practices, as illustrated by their microloan program. Hmong people have a deep aversion to debt, which can inhibit their ability to finance large investments in land or equipment. To address this hurdle in a culturally appropriate way, HAFA created a matched savings account in which members could have their investments matched by the organization. This allowed members to leverage their savings and reduce debt risk while accessing funds to purchase a needed tractor or truck. In the four years since HAFA launched their farm business and food entrepreneurship program, it has helped secure more than $200,000 in equipment for its members.

HAFA’s leadership also quickly identified that their members’ well-being and prosperity are inextricably tied to the overall physical and economic health of the broader community in which they live. In 2016, they developed multi-year, multi-sector partnerships to increase access to healthy, locally grown produce among anchor institutions on St. Paul’s East Side, where the majority of HAFA farmers live.

Institutions including Dayton’s Bluff Community Council, Metropolitan State University and Merrick Community Services agreed to buy produce from HAFA to use in meals, educate families about healthy eating, and change practices and policies to emphasize local procurement. The HealthEast Care System now distributes HAFA’s CSA boxes to some of its most food insecure patients, and St. Paul Head Start gets almost a quarter of its produce from HAFA farmers, in addition to sending more than 120 kids to tour the farm each year and learn about sustainable agriculture and healthy eating.

Conquering Challenges Through Collaboration, Innovation and Inclusivity

Hang describes the five “spokes” in the wheel of HAFA’s economic development model, which addresses each of the obstacles faced by Hmong American farmers: access to land, access to new markets, business development, training and research. “Each spoke is necessary for the success of HAFA’s mission but none is sufficient in themselves,” says Hang. “You need them all in order to roll.”

Elena Gaarder (BF’15), program officer for Nexus Community Partners, has been working with HAFA since 2013 when Nexus started funding HAFA through its grant program. She views the organization’s work through the prism of the Whole Foods Model, which centers on building a value-based food system that emphasizes equitable incomes for farmers and workers, ecological sustainability, and community building capacity.

“According to the Whole Foods Model, it doesn’t matter if you have access to land if you don’t have access to capital,” explains Gaarder. “Without a business plan or alternative markets, you can’t grow your profits. The HAFA Farm addresses the land access issue, but the organization has also been examining all parts of the local food ecosystem, identifying barriers and then addressing them to build intergenerational wealth and expand broad-based ownership.”

Self-efficacy is a central operating value at HAFA; its members are the lead decision-makers, innovators and problem-solvers. “HAFA is membership-based, which is a departure from our peers (nonprofits that serve immigrant farmers),” says Hang. “In order to benefit from our programs, you have to join — be a member. We wanted people to understand you have to be part of the solution. We can build technical skills and allow them to build capital and buy a tractor, but if they’re not primed to think differently and build an economic framework and consciousness, we won’t really move people.”

What’s truly innovative about HAFA’s model is the way it encompasses the entirety of that economic framework and empowers its members. It’s not only about providing material and logistical business needs. It’s also about imbuing the kind of training, resourcefulness and capacity building that can create a paradigm shift in a community, rippling down through the generations like a perennial crop that grows in bounty each season.

“Everything is tackled and looked at through HAFA, as opposed to just a couple of trainings here and there or a little land,” says Janssen Hang. “We emphasize the concepts of land tenure, diversifying income and business development, and help our members ask, ‘How do I improve my business and change my mentality?’”

To ensure that this capacity building continues to grow stronger with each successive generation, HAFA requires member farmers’ children to attend trainings and assist with tasks such as writing food safety and business plans. And many of the farmers’ children have helped spearhead a value-added program, in which they purchase produce from their parents and use it to create additional revenue-generating products such as carrot cake or jam.

“True economic development is lifting up families and building intergenerational wealth,” says Hang. “You start by addressing income, but ultimately we’re focused on building sustainable wealth, which means focusing on children in addition to their parents.”

When asked what success looks like for HAFA, Hang says it will be realized multiple generations from now. “Success will be a Hmong American farmer in charge of a multifaceted corporation saying they got their roots from their grandparents, who were HAFA members — that this was the seed that built their family’s dynasty. The way the future views the past will be how we judge our success.”